Ticks: Year-Round Threat to Horses

Cold weather may have horse owners pushing their fly repellent to the back shelf. Ticks, however, pose a year-round risk. The National Equine Tick Survey underscores this ongoing concern.

“In the NETS study, we collected ticks from horses every month of the year. This highlights that there are seasonal variations in tick abundance or the species that is most active, but there are no ‘tick-free’ months. Ticks are most definitely a year-round issue,” notes Brian Herrin, DVM, PhD, assistant professor of veterinary parasitology at Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine.

In fact, some species are active specifically during the fall and winter, not spring or summer.

Herrin points out that adult Ixodes scapularis is a cold weather tick, most commonly found in October and November, while Dermacentor albipictus emerges in December and January, making it a true winter tick.

Cold weather tick risks

Not all ticks feed on horses. Of those that do, the following North American species are active during cold months.

Winter Tick (Dermacentor albipictus)

Active season and range: winter, across North America Threat to horses: irritation, blood loss due to high numbers in one infestation

Blacklegged Tick (Ixodes scapularis) sometimes referred to as “Deer ticks

Active season and range: fall - winter, Eastern U.S. Threat to horses: Lyme disease, Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis

Western Blacklegged Tick (Ixodes pacificus)

Active season and range: fall - winter, Western coast U.S. Threat to horses: Lyme disease, Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis

(Note: Blacklegged ticks and Western Blacklegged ticks look identical to the naked eye. Precise identification requires microscopic examination or DNA analysis.)

Spinose Ear Tick (Otobius megnini)

Active season and range: year-round, Western U.S Threat to horses: severe irritation in ear/ear canal can impact behavior

Large tick burdens

In the NETS study, the greatest number of ticks collected were of the species Dermacentor albipictus, also known as the Winter Tick or Ghost Moose tick.

Herrin notes that those ticks came from a few horses that were heavily infested. In fact, one single horse had a tick burden of over 800 ticks!

“Some interesting things about this tick are that it is out in the winter and ALL life stages are on the host (horses, cows, deer, moose) at the same time. Meaning the infested animal can have thousands of ticks on it at once,” explains Herrin.

“While it may be shocking to horse owners to suddenly find their horse completely infested with ticks, usually one treatment with an appropriate topical product is sufficient to clear the horse of the ticks,” says Herrin, noting that ticks rarely return until the next winter.

Protecting horses

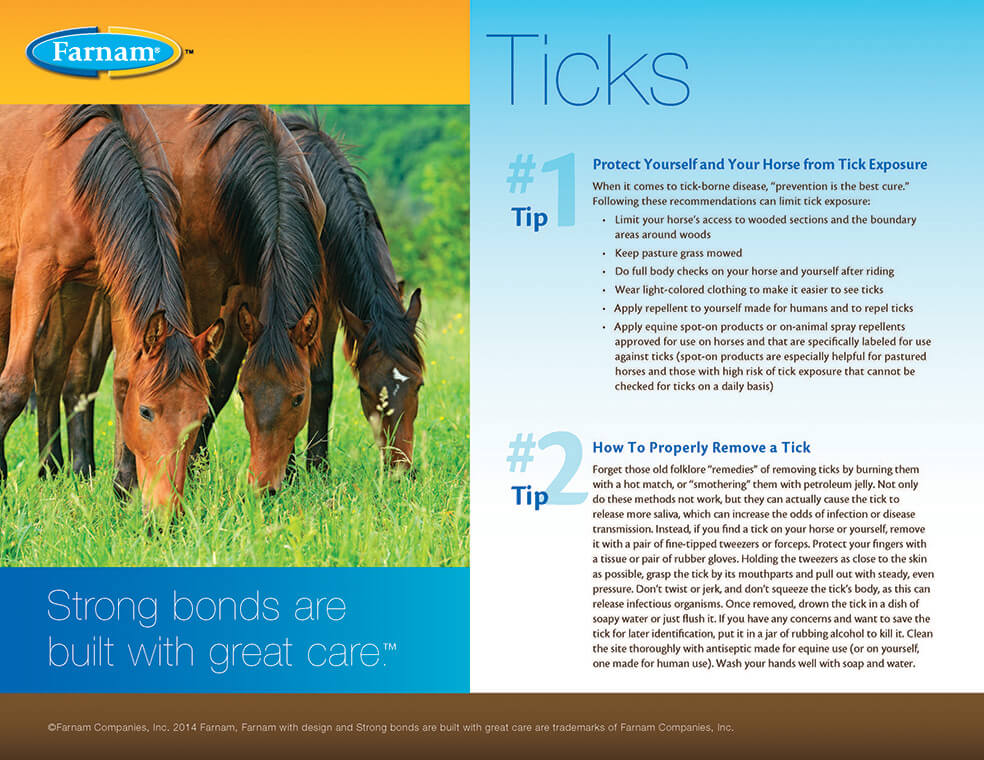

Ticks don’t like open, bare sunny areas, but prefer shade, woods, tall grass, and layered vegetation. If you ride in such areas, or keep your horse in these conditions, the risk of tick exposure increases.

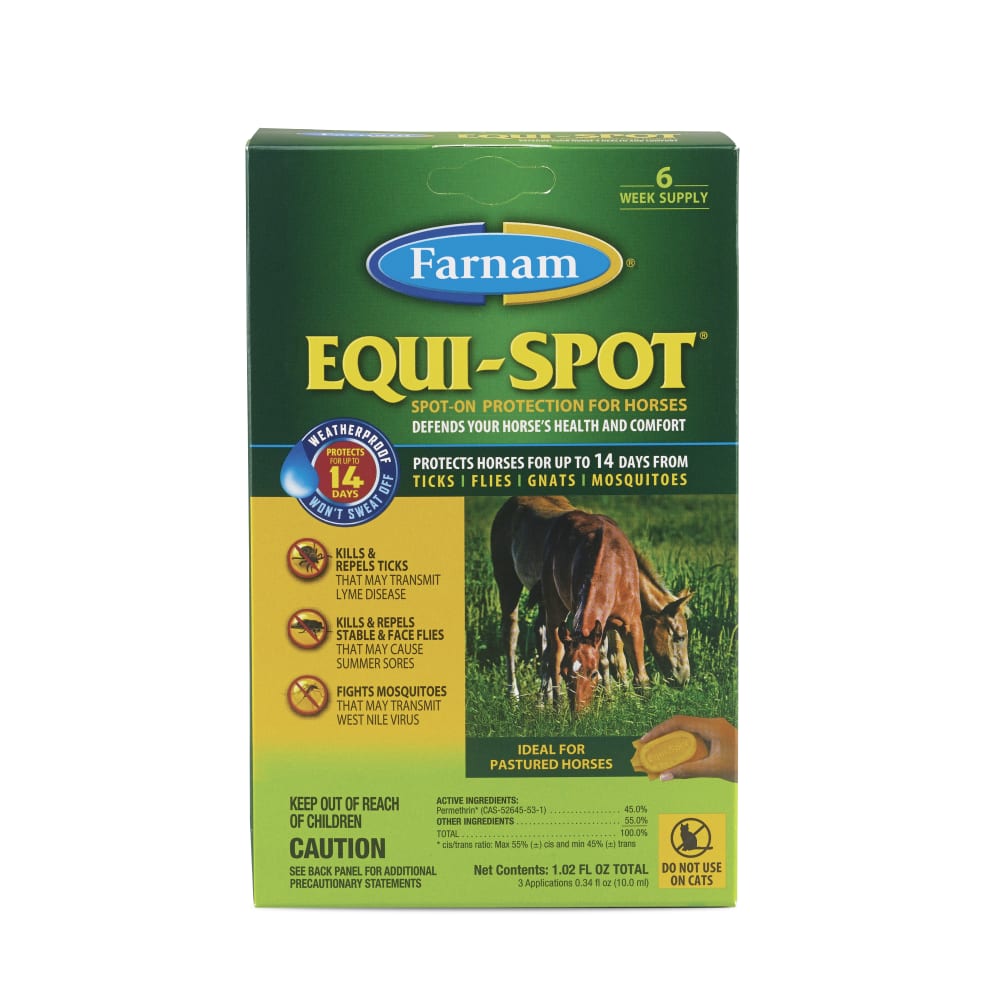

For safety’s sake, apply on-horse repellent product that protects against ticks right before riding, especially when you’ll be in tick-infested areas, like woods. Spot-on topical products are especially practical for horses that live outside 24/7 and aren’t groomed daily.

Check for ticks

Even if you have applied an insect repellant to your horse, it’s important to do a thorough “tick check” after your ride. Check for ticks regularly if your horse is pastured in an area where ticks are present.

“Vigilance is the best method to keep horses safe from ticks,” says Herrin. “Ticks love to hide, so remember to check the horse’s chin, armpits, groin, and base of the tail.”

Remove any tick you find by using fine-tipped tweezers to grasp it by its head/mouthparts as close to the horse’s skin as possible. Pull the tick straight out with steady pressure. Don’t jerk or twist it and don’t squeeze the tick’s body. After removal, clean the area with rubbing alcohol.

Learn more about the NETS study findings and ticks of concern to horse owners at equineticks.com/what-we-do.

Did You Know?

Avoid ill-advised tick removal methods, such as “smothering” them with petroleum jelly or nail polish or burning them with a match. Any removal method that damages the tick can potentially force more bacteria and infectious agents out of the tick’s body into the host. Plus, you want to remove the tick as soon as you find it. The longer it’s attached, the greater the odds it can cause damage and/or transmit disease.

Did You Know?

If you have a dog, you’re likely using a spot-on product to protect against ticks and fleas. Don’t assume you can use canine spot-on products on horses. Such off-label use is illegal and not recommended. Instead, use spot-on topical products specifically made for horses.

Life with Horses Newsletter

Sign up now to stay connected with free helpful horse care tips, product updates, and special offers.